If you’ve been a woman for a while, and attempted whilst afflicted by visible womanhood to participate in the doings of human society, it is probably no momentous revelation to you that men can be creepy, coercive, threatening, tyrannizing, and gross. Not gross in the sense of unwashed hands and very terrible smells breezing into one’s life from other people’s lunches, but gross in that “I will corner you at the office party and make you regret ever leaving your house today, ever leaving your house at all, ever living” sort of way. Is there a woman alive today who has not been harassed by a man, at work, at school, while riding a train or bus or while walking down the street, sitting in a park, shopping for produce at the grocery store, breathing the air in a place outside her own home? I would love to meet this woman if she’s out there, to talk with her about what it’s like: to feel you can move through the world freely because you are not its prey and you do not fear it will devour you. Since I’ve not yet known a woman who hasn’t been harassed or made to feel uncomfortable or far worse by a man while she was trying to do something rather basic like maybe her job or maybe just existing in public, however, I have trouble believing that any woman could be genuinely alarmed to learn that Harvey Weinstein, Louis C.K., Dustin Hoffman, Charlie Rose, Al Franken, Matt Lauer, Artforum’s Knight Landesman (evidence that Male Scum Syndrome is not a blight exclusive to the middlebrow) etc., etc., etc., did the creepy, coercive, threatening, tyrannizing and gross things that they did to women.

We have no cause for alarm. Men harassing women sexually – and to be specific: high-powered men harassing their young, hungry-to-succeed female subordinates – is as unsurprising as a white supremacist state’s police force routinely murdering black citizens. It is as unsurprising as endemic poverty in a capitalist paradigm. These are the symptoms of the structural realities of our society and they should not be news to anyone has not been in a coma since birth. They are devastating. They are not surprising.

The surprise is that suddenly there are consequences for the men. All those little “indiscretions” buried to fester under the oversized rug patriarchy supplies its loyal henchmen have made like revenants and clawed their way risen to the surface to haunt the guilty. Powerful men are being ousted from their positions of power. They are being reviled and banished. Recovery seems improbable. The major shocker is that women are bringing men down for a change; women are being believed instead of dismissed as desperate for attention, denounced as psychotic schemers, or blamed for enticing abuse; the harm done to women by sexual harassment has neither been shrugged off as trivial nor laughed away with the usual lewd sneering. It is as if what men do to women, and how men’s actions reverberate through women’s lives, is of some actual significance. As if it is not women’s ineludible doom to be reduced to sexual chattel whenever we dare venture out in public.

And this is surprising, and this is good. Even if it is only a symbolic purge submitted by the Nice Good Liberal (male-dominated) Left as a safeguard against looking severely hypocritical subsequent to its politically pragmatic show of appalled horror over Donald Trump’s I’m-the-Boss-Man handsiness, it is nonetheless good. Let’s call it progress.

The #MeToo campaign is a product of this freakish and pathetically unprecedented moment in which it would almost seem that a woman can expect to be listened to when she speaks about what men have done to her. Women have come forward online in droves to share their stories of sexual intimidation and coercion by men, the publicization of our collective victimization cascading out to overflow the Internet, as the dams give way under the wash of horror stories: each woman who speaks out grants another woman license to speak, and what woman doesn’t have a story she could tell? #MeToo has the potential for infinite growth. If every woman ever harassed or assaulted by a man with power over her announced to the world how she was abused, the thread could mushroom on and on forever. Maybe it should. There is an urgency to sharing these stories, their public airing a corrective to the silence that women have been paid off for or terrorized into. Our own shame has forced us into silence, too. It is disgusting to have to put words to what men do to us, the vileness of their offenses such a stain inside accusing our own bodies our own selves of badness that we long to forget them immediately, even as they are happening, and to never mention them again afterwards—they are unspeakable. And we have stayed silent because we have been afraid. Afraid of the repercussions of speaking. Afraid of not being believed. For the many women for whom #MeToo has been a release from silence, and for every woman unwilling to accept silence in the future, having seen a million sisters before her raise their voices, the value of its impact cannot be overstated.

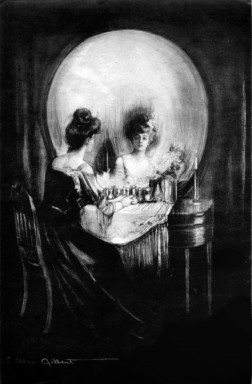

Yet I was reluctant to join the #MeToo chorus. I watched other women broadcast their experiences, cheered, at first, that women were catalyzing a long overdue reckoning with the scourge of sexual harassment, but as the atmosphere grew increasingly #MeToo-saturated, an old wariness edged in to replace my optimism. I still appreciated the women who added their accounts to the deluge and I remained encouraged that women felt newly supported in outrage over the everyday sexual violence and exploitation that gives form to Existing While Female in a patriarchy, but, as the Internet filled to capacity with the grim details of harassment, assaults, abuse, rapes, I began to sense with creepy-crawly acuteness something unsavory latent in the media’s receptiveness to all of these stories, all of these women telling them. I wondered: what is the social function of women’s admission of sexual trauma? There’s a market demand for this stuff. Women’s personal revelations of painful, and especially painful sexual experiences have a long history as a tantalizing cultural commodity, to be dished up lurid, with a garnish of theatrical shock and solicitude on the side. If women start talking, these are the tales we’re supposed to be telling. They sell. It’s true that women have been silenced but our silence is not the whole story. Women do not in fact go around all the time with ball gags lodged between our lips. Muzzling women is the bluntest way of ensuring that female subjectivity does not contaminate precious masculinist cultural real estate; it is the most obvious strategy but not the only, or necessarily the most effective option at patriarchy’s disposal. Circumscribing the range and manner of women’s speech is a subtler tactic, a nicer, less glaring suppression, useful for its preservation of the exigent illusion that women are free to do as we please and just happen to end up an underclass because – ain’t it the weirdest thing? – such is our nature. Many women stay mute, but there are plenty of us who speak. And that is all well and good, on the condition that what’s coming out of our mouths are nuggets of “realness” razored from the deepest recesses of our private lives, the darker the better, warm still and glistening with gut-blood. Continue reading “#MeToo, Disclosure & the Confessional Mode”