The anguish of the world is on my tongue.

My bowl is filled to the brim with it; there is more than I can eat.

(Edna St. Vincent Millay, “The Anguish”)

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution’s power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

(Edna St. Vincent Millay, Sonnet XXX)

Edna St. Vincent Millay was a poet and playwright; in 1923, at 31, she won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, she was terrifically famous, and today hers is one of the few women’s names anyone can summon when asked to identify a female writer. When I think of Edna St. Vincent Millay, I think of delicate poems of longing, bucolic melancholia, the pains and pleasures of female desire in a phallocentric universe, the inescapable hours and years altering the green of spring’s bowers to ash on your palm, whose skin is fated to shrivel and dry to the bone, your bones washed bare on the shore of the endless sea and the small soft music of your life hung a coil of light from the crescent moon, as dusk settles, violet-streaked. I think perhaps of candles weeping their last tallow at 3am and fruit held in my mouth until it is liquid and I swallow it. I do not think of black lace lingerie. The memory of Millay does not rouse in me a ravenous appetite for new “undies” or satin robes. (“Undies”? I have not wanted “undies” since I was nine, but we’ll have to ignore the infantilizing language for now and move on.)

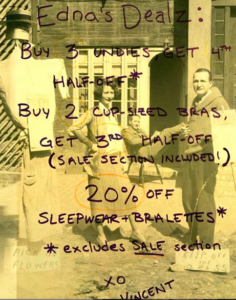

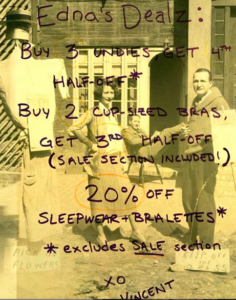

So, when I noticed large photographs of Millay’s head floating around in the display window of the local lingerie boutique, her head taped to the neck-stumps of limbless mannequins dressed in lace maillots and peignoirs as if the boudoir-ready limbless mannequin were Millay herself, I was at first puzzled. For a fleeting moment I was a prey to my naivety and the connection between a bra sale and the poet eluded me. Although I have by no means read everything that Millay wrote, I’ve read enough to know that underthings were not a major motif in her work. She referenced ribbons in her hair and spoke archly of “pleasing lads” with such decor, but if she had ever penned an ode to the bralette, I missed it.

What I’d forgotten, for a moment, was that Edna St. Vincent Millay was a woman, and that womanhood alone is enough to convert the female artist into a lingerie boutique’s spokesmodel. In a patriarchal world, women are sex (Simone de Beauvoir said it and I’ll carry on saying it until it’s no longer true). The female artist is therefore an object of predominantly sexual interest; her flavor, as sex object, is “artistic.” If sexuality is a subject of her art, as it was for Millay, and which it will be for many women artists, because sexuality is inevitably central in the life of someone raised to incarnate sex, her course to the Sex Symbol pedestal will proceed all the more smoothly. In a capitalist world, sex is reduced to commodity, and sold to women, who are sex, as lingerie. Thus the tether that connects Woman Artist and Lingerie Model is a constant specter. A woman is a Woman no matter what else she may be and we all know what the world wants from her. It is charming enough if she makes art, if she has a talent, but that is not the core of her; at her core, she is sex. Our culture strips her, to delve to the core: we are to wonder what color panties the painter preferred, to gossip about under what conditions the poet lost her virginity, and did she wear silk stockings, and how many black rosettes crowned the curve of her breast.

I can only assume that it was women who decorated the window of a lingerie shop with a bevy of Edna St. Vincent Millay black lace sex mannequins. Women sell women lingerie: our conditioning is more effective if it is promoted as “women’s culture,” the influence of men rendered invisible. Much of the bullshit that degrades us we learn to do and to cherish from other women, who learned from other women, who learned from other women the terms of our lives within a male-ruled society. It is women who write romance novels and diet guides; it is our mothers who teach us to mind our manners. Where female genital mutilation is practiced, it is women who perform the cutting. Such is “cultural tradition”—but one is compelled to inquire: whose culture is it, at base? A woman may hold the blade, but who instructed her in the art of cutting? I assume that the women involved in the lingerie shop’s Millay display imagined they were paying tribute to the poet by offering discounts on their wares in her honor and proudly taping her head up in their window. And I assume, too, that they figured it would be a clever and unconventional way to sell women expensive sexual accessories, lending their store a certain artistic, pro-woman if not feminist mystique, for they were appreciating a brilliant and accomplished – not merely a beautiful – woman. This is a good marketing strategy; we fall for it again and again, because we want to be brilliant, certainly, but that alone does not fulfill us, for we know our true worth to be in beauty, desirability; we desire our brilliance to be what makes us beautiful: the poetry I write becomes an intellectual negligee I flaunt when I long for someone to love me. Just as I have sold myself short, as we sell ourselves short, as capitalist patriarchy has trained us to sell ourselves, the lingerie boutique sold Edna St. Vincent Millay: the Woman Artist as sexualized commodity, her image exploited to peddle sexualized commodities (bras and chemisettes) to women, so that we might venture bravely out into the world as sexualized commodities. It seems terribly cynical, yet it was not, or not consciously: I do not question that the lingerie-mongers were sincere in seeking to celebrate Millay, and their exploitation of her is all the more disturbing for their good intentions: it reflects a self-exploitation so engrained in us as women that we scarcely notice when we do it to other women. We have come to call this carving ourselves distorted into consumable objects on display “loving” ourselves. Yet I do not believe Millay would have been pleased by the “honor” of seeing herself so reduced. I believe she knew herself to be something more. I hope like hell she did, in any case, and I hope that someday we all may recapture that knowledge.