The British photographer David Hamilton, whose long career treated art appreciators and men everywhere to over twenty books bursting with soft-focus images of naked pubescent girls, died last week at age 83. It’s possible that he took his own life, as there are reports that when found in his Paris home by a neighbor, Hamilton had a plastic bag drawn over his head, a bottle of pills nearby. Perhaps, struck by a sudden, winter-of-the-soul realization of his role in normalizing – and providing fodder to fuel – the sexual objectification of girl-children by adult men, or of his own creative bankruptcy, Hamilton could no longer bear to live with himself. Or maybe he pulled the plastic bag over his head because four women had recently come forward with accounts of how Hamilton raped them when they modeled for him as children, and he could not bear the smear of being outed as a sexual predator. Since men’s consciences seem only rarely to suffer for either their crimes against females or for burdening the world with bad art, I’m going to say the latter is a safer bet.

Shortly before his death Hamilton denied the allegations against him, claiming he had done “nothing improper” and “nothing at all,” and threatened to sue one of the women, Flavie Flament, for defamation. In October, Flament published a semi-autobiographical novel in which she describes being raped by a famous photographer. Following the novel’s release, when she began to hear from other women whose experiences with said photographer mirrored her own, she publicly identified Hamilton as the “man who raped [her] when [she] was 13, the man who raped many young girls.” Since his death, Flament has charged the dead artist with cowardice for suiciding and depriving his victims the closure of ever seeing him convicted.

She is right that it was cowardly for Hamilton to abdicate responsibility by excusing himself from earthly existence. I wonder, however, if this act of cowardice is not such a sorry outcome. Are we to regret that he died? Frankly I am not up to the task of mourning his death. If he ought to have lived in order to be condemned, well, the majority of rapists escape conviction and in any case, under the French statue of limitations, the charges against Hamilton were too old to be tried. He never would have been convicted. And while I sympathize with the women’s desire to see their rapist treated as a criminal, I also question whether or not the established route of trial and penalty always, or ever, achieves real justice. With his suicide, Hamilton sentenced himself to death, a choice that rings of confession. Would an innocent man kill himself over false accusations? And what was he so afraid of, if not being known for what he was: a man who raped young girls? Hamilton’s suicide intimates his guilt, and although he is not here now to face the consequences, we can hope that the new posthumous stench of culpability will taint his artistic legacy.

To solve the David Hamilton problem, the repudiation of not only Hamilton the man (i.e., the rapist) but Hamilton the artist is necessary. Even if Hamilton had not raped the girls who modeled for him, and I have zero doubt that he did rape them, he still did something “improper.” He did not do “nothing at all”: he took his awful photographs, and he made his films. A thousand images of limply sprawled young girls laid out to be plucked up off the futon or flowered field by some lurking predator. His art in itself is an assault, and as long as it and its upscale pornographic kin are defended, championed, passed off as harmless kitsch and “eroticism” and “celebrations of beauty,” there will be no justice, not for the girls Hamilton raped, not for any girl who has been or will be raped, not for any girl.

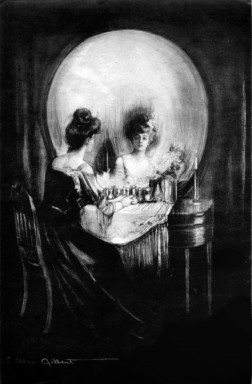

I confess I own one of David Hamilton’s books. Be assured I did not buy it. Rather, I unearthed it from the donations bin of the library where I worked, buried down amidst the standard Tom Clancy paperbacks and Atkins Diet cookbooks. I hadn’t heard of Hamilton but I knew immediately from the cover that this book, with its glossy photo of two topless blonde teenagers laundering their gauzy shifts? preparing a bath? inside an egg of golden light, that this was not suitable merchandise for the Friends of the Library book sale. The title was DREAMS OF YOUNG GIRLS, Hamilton’s 1971 debut, a collection of photographs of girls, very, very, very young, in white stockings and sheep pastures and frolicking and creeping nude along the misted banks of burbling brooks, and sleeping, or pretending to sleep, collapsing into trance-like passivity in shadowed alcoves, in sun hats and sundresses, innocently inspecting the naked bodies of their playmates as they pass endless afternoons staring out the windows of the chicly frowzy summer villa, like a lace-and-wicker detention facility, where they have been interred. The photographs are accompanied by poems penned by the French novelist and filmmaker Alain Robbe-Grillet, upscale misogynist and, unfortunately, highly influential personage of postmodern lit.

I could not linger over DREAMS OF YOUNG GIRLS at the library, a flipping through its pages having made clear to me the content was NSFW, but it was too perfectly vile for me to leave behind. I did not want anyone else to find it and take it and possibly masturbate over it; I did not want the book to exist and so in a not entirely rational attempt to evict it from the universe I hid it in my backpack and took it home with me, where it could not fall into the “wrong hands,” i.e. the hands of anyone who would not categorically reject it as child pornography.

Hamilton’s work is child pornography. This is its basic evil. It sexualizes pre- and only barely pubescent girls as objects for the male gaze, which is never sated by “just looking.” An object is created to be possessed; the sexual object is possessed sexually. Thus it is no particular shocker that a man who took a million photographs of young girls’ developing breasts would also rape the young girls he photographed. Like all child pornography, the fantasies Hamilton’s work fosters place girls at risk of violation.

It violates girls in another way, too: by denying us ownership of our own dreams. The title DREAMS OF YOUNG GIRLS is purposefully, playfully ambiguous in how it suggests both the stuff of young girls’ dreams and the dreams that non-girls (see: men) have about young girls. Yet what girl dreams about dozing naked next to a wash basin, of undressing before an open window? These are men’s dreams, but because men control cultural production, men can cast them as the dreams of girls. That many of Robbe-Grillet’s poems are written from the perspective of a girl – “My name is Suzanne./I am naked, yet virginal./I am innocent and hard./My eyes are blank.” – is evidence of how blithely culture concedes the territory of female subjectivity to male creators. Men’s dreams about young girls become girls’ dreams, indistinguishable; men’s dreams infest us and displace our own, men’s meanings for us supplant our own meanings, until we we have nothing of ourselves, and we dream of being what men desire us to be. Which, if DREAMS OF YOUNG GIRLS is any indication, which it is, we emerge from cooption dreaming of being 14 and eminently vulnerable, held captive in some rich asshole’s summer house.

Tragically this seems not far off for many girls and women.

It is bad that men like David Hamilton can build art careers romanticizing the sexual exploitation of young girls. It is worse that the images of young girls these men produce, as sanctioned culture-makers, come to define what a girl is, what a girl can be, and what it means to be a girl, in men’s dreams and in our own. Hamilton may be dead, and he may be publicly reviled as a probable rapist, but the image of girlhood he so prolifically contributed to constructing lives on, and it will persist, parasitic, until we forcibly oust it.